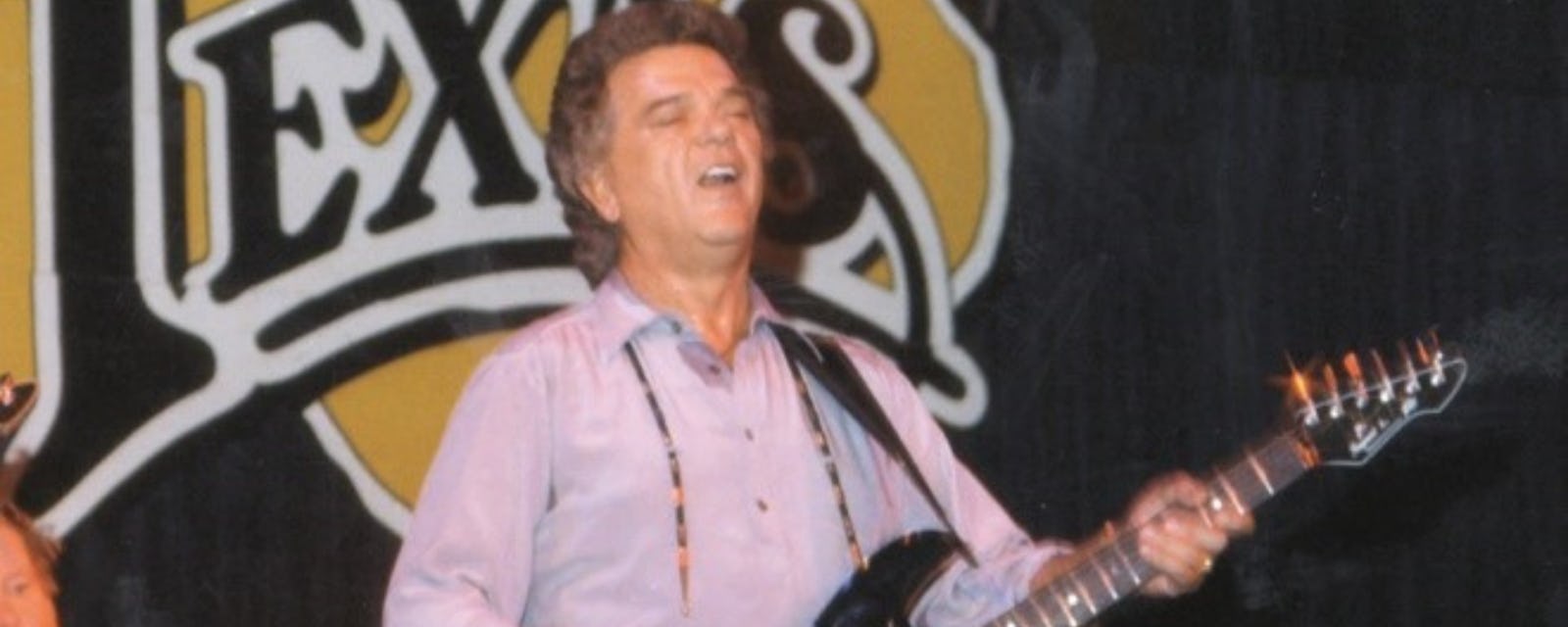

Conway Twitty

HISTORY WITH BILLY BOB’S:

Country Legend Conway Twitty died June 5, 1993, only a few weeks before his scheduled performance at Billy Bob’s on June 26. With many tickets for the show already sold, Skip Ewing performed a tribute to the late singer. Ticket holders were allowed to enjoy the for free, and were also offered a refund of their tickets. Around 50 percent of the concert-goers did not ask for a refund so they could keep their ticket as a memento.

ABOUT CONWAY TWITTY:

By any measure, the career of singer, songwriter, producer, entertainer and recording artist Conway Twitty stands among the greatest in the history of popular music. His 55 No. 1 singles are an astounding and singular accomplishment in the annals of the recording industry. Those hits drove sales of more than 50 million records, powering literally thousands of live performances for tens of millions of fans, and led to more than 100 major awards.

Numbers, however, don’t tell the whole story. They don’t even tell the most important part of the story. Because in Conway Twitty, the world has a refreshing example of a natural — a natural athlete, a natural singer, a naturally caring and charismatic person who never took his abilities for granted. Instead, Twitty respected his gifts by working at them, and by respecting everyone he touched. There is no tortured artist in this story. There is no grand comeback from the brink of self-destruction. Just the remarkably steady journey of a man who never drank, never used drugs, but simply worked hard at what he loved, a family he loved deeply and the fans that cared for him.

From Sun Studios in Memphis and the infancy of rock and roll to the top of the country charts and induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame, Conway built an astounding musical legacy that spanned five decades. The truest assessment of that legacy will never make it onto history’s pages, however, because it is written on the hearts of everyone he knew and everyone who knew him through his music. This is Conway Twitty. Even as a small child, it was apparent there was something special about Twitty. Born Harold Lloyd Jenkins on September 1, 1933 in rural Friars Point, Mississippi, the boy had uncommon abilities and a penchant for helping those around him.Given his first guitar, a Sears & Roebuck acoustic, at the age of four, Harold demonstrated a musical gift. He formed his first band, the Phillips County Ramblers when he was 10 after the family had moved to Helena, Arkansas. His mother was the breadwinner and his father found spotty work as a Mississippi riverboat pilot. Harold obtained employment as a carhop and used his earnings to buy clothes and shoes for his brother and sister.

When one of a group of friends horsing around in a local cemetery was pinned under a fallen tombstone, young Harold started to flee with the rest of the frightened pack of boys. He stopped short, however, returning to assist his friend and lifting the stone enough for the boy to scramble free. When the full group returned the next day to reset the stone, they marveled at the feat, as the entire group of them were unable to lift it.

He landed a weekly radio show, and in his other passion, baseball, developed his skills to the point of playing semi-pro and being offered a contract by the Philadelphia Phillies after high school. Jenkins figured his destiny was decided when he was drafted by the Philadelphia Phillies. Fate intervened, however, when he was drafted by a much bigger team — the U.S. Army. While stationed in Japan, he kept both his dreams alive by forming a band and playing on the local Army baseball team. The band was called the “Cimmarons” and played at different clubs. After his release from the army it was the mid 1950s and the sudden popularity of a young man named Elvis Presley drew a still very young Harold Jenkins to Memphis.

While recording at Sun Studios with Presley, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis, Jenkins began developing a sound that would lead to a record deal with MGM. He also took a stage name, contracting the names of two cities — Conway, Arkansas and Twitty, Texas. In 1958, Conway Twitty scored his first No. 1 hit titled “It’s Only Make Believe.”

His career as a rock-n-roll act took off, with the single topping the chart in 22 different countries and going on to sell eight million copies. Despite making a name for himself as a rock n roller, Twitty had always loved country music. In fact, his reverence for the genre and its seasoned performers factored into his decision to become a rock n roll performer. Twitty also enjoyed a short-lived movie career, appearing in films like Sex Kittens Go To College (with Mamie Van Doren), Platinum High School (Mickey Rooney), and College Confidential (Steve Allen) and writing the title and sound track songs for the films. A play and movie was created titled “Bye Bye Birdie” which was a story about a young rock-n-roll star. It was written with the idea that Conway would do the starring role. The lead character’s name, Conrad Birdie, was created specifically with Conway in mind. Conway did a lot of soul searching and decided that theatre and the movies were not for him, so he turned down the offer and remained focused on his true love of music.

At first, rock n roll seemed to be a place where a young man with a lot of raw talent could thrive. Through his early recording and touring (including three gold records), Twitty got to know a fair number of country stars, eventually abandoning his insecurities so he could “compete with my heroes.”

After eight years of playing sock hops and dance clubs, Twitty heard the ticking of an internal clock that seemed to guide all the major decisions in his life. One night on a stage in Summer’s Point, New Jersey, Twitty looked out at a room full of people he didn’t know. With a wife and three kids at home, he realized his days of providing background music for sweaty teens were over. Twitty put down his guitar, walked off the stage and embarked on one of the greatest country careers in history.

Signed by legendary producer Owen Bradley to MCA/Decca in 1965, Twitty released several singles before 1968’s “Next In Line” became his first country No. 1. And thus began a run unmatched in music history. Twitty reeled off 50 consecutive No. 1 hits.

Widely regarded by Nashville’s songwriters as “the best friend a song ever had,” Twitty was pitched top shelf material for the better part of two decades. Much of it he turned away, even passing eventual smash singles on to other artists. One of his many gifts, beyond the elusive art of

knowing which songs would be hits, was knowing which of those songs would work for him. Of course, he was one of Music Row’s best songwriters in his own right, writing 19 of his No. 1s and earning Grammy nominations for compositions including his signature song “Hello Darlin’.”

Twitty’s tunes are the mile markers for three decades of country music: “Hello Darlin’,” “Goodbye Time,” “You’ve Never Been This Far Before,” “Linda On My Mind,” “I’d Love To Lay You Down,” “Tight Fittin’ Jeans,” “That’s My Job.” Conway also entered into a duet partnership with the top female vocalist of that time, Loretta Lynn. They became the most awarded male/female duet in history recording with songs like “After The Fire Is Gone,” “Lead Me On,” and “Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man

His way with hits extended beyond writing, choosing and making great records to arranging them in a way that brilliantly paced his live performances. As an entertainer, he was a master of understatement and mystery who was nicknamed the “High Priest of Country Music” by his peers.

He avoided onstage banter in favor of a tightly woven journey through his beloved hit songs. “I’m often asked why ,” Conway said, Why don’t I talk at my concerts. My answer is always the same. I do talk, but the communication is through my music” Conway said.

His voice even reached into outer space when “Hello Darlin” was played around the world during the link up between America’s orbiting astronauts and Russia’s cosmonauts in a gesture of international good will.

Twitty had a tremendous respect for women and sang many of his biggest hits directly to them. By choosing to perform songs with adult themes, many of which were controversial at the time, he built a passionate fan base. Perhaps the most dramatic example of this is illustrated by a California performance where an audience member suffered a heart attack. The woman refused paramedic’s urgings that she accompany them to the hospital, saying she wasn’t leaving until she heard “Hello Darlin’.” A note was passed to the stage and Twitty performed the show closer earlier than planned so his fan could receive proper medical care.

Despite such adoration, Twitty remained a genuine and unpretentious person. He regularly stayed hours after his shows signing autographs, once staying so long as to be engaged in a discussion with the venue janitor as his bus left without him. At home, he drove an old Pacer station wagon and favored jogging suits and ball caps. On many occasions people would stop him and ask if he’d been told he resembled Conway Twitty. “I’ve heard that,” he’d reply, “but I don’t see the resemblance.”

In 1982, Conway opened one of the largest tourist attractions in the state of Tennessee. Twitty City, located north of Nashville in Hendersonville, was a true testament to his deep love and appreciation for his fans. Hundreds of thousands of them roamed the grounds year round, taking in views that included the mansion of Conway and his wife, Mickey, the home of his mother and the homes of his four adult children. The Twitty City complex also included Conway Twitty Enterprises, a gift shop, a

theatrical showcase of Conway’s life, beautifully landscaped grounds with water falls and a pavilion area.

His love of Christmas led to an annual light festival that eventually included live reindeer, snow machines and millions of visitors. Twitty donated proceeds from tours of the grounds to help the families of local fallen police and firefighters. Another regular event was a Christmas For Kids concert that raised funds to help underprivileged children. He also built a ball field for the local Little League that still bears his name.

Giving back was not simply a reaction to his wealth, however. It was part of his nature. In the early rock days when he was barely clearing enough money to cover expenses, Twitty was approached at a truck stop by a man asking for $20 so he and his pregnant wife could buy enough gas to return home. Twitty gave the man $200. Years later, Twitty and his children were dining at a restaurant in Oklahoma City when a man asked to speak to the star. Twitty’s children watched their father talking quietly with the man, and saw him grow misty eyed as the man handed their father an envelope.

Despite Twitty’s insistence that the money was a gift, the man from the truck stop was determined to repay him.

Charitable endeavors were something rarely discussed. “If you have to talk about it, it’s not from the heart,” Twitty would say. And though his pairing with Loretta Lynn was one of the most celebrated duets in history, he never complained that the Country Music Association never recognized him with an award for his accomplishments as a solo artist. “Each one of my fans is enough of an award for me,” he’d say.

Nevertheless, he was a hard working, determined and quietly ambitious man who believed he was called to do more than rest on his God-given abilities. And so he pushed to evolve his gifts, driving to improve upon his last album, to record another smash, to break another concert attendance record. In 36 years of touring, he never missed a show — an example of consistency that, to use an analogy from his favorite sport made him a musical DiMaggio or Ripken. This came from a man who would turn down so much as an aspirin, and coming out of an era when entertainers were often encouraged to medicate by their own traveling physicians.

Asked in the midst of his incredible streak what he’d do if one of his songs didn’t reach No. 1, the unassuming Twitty replied, “I’ll just start over.” And when the follow up to “Don’t Call Him A Cowboy” peaked at #2, that’s exactly what he did — scoring five more chart-toppers, the last being “Crazy In Love,” before his untimely death in June, 1993. His last album, Final Touches, was released after his death later that year.

If there’s an unfortunate addendum to Twitty’s story, it is that his place in the history of country music has largely been overlooked. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1999, but a legal battle over his estate kept his sons and daughters from endeavoring to tell his story for almost 14 years. Until now.

And yet as they begin work on the reissues, the box sets and the retrospectives so long overdue, they are continually reminded of the foundation upon which their father’s unparalleled achievements were built. Those who worked with Conway, knew him or were influenced by him approach with stories of a true gentleman, someone who, as one fellow performer described him, “wore a white hat.” Throughout his life, Conway would tell people, “If you do what you love and you’re able to take care of the people you love, it doesn’t matter what you do. You’re a successful man. ” Undoubtedly, that is the legacy that would have meant the most to Harold “Conway Twitty” Jenkins. Which makes the rest of his story — the accomplishments and accolades — that much sweeter.

Debut Date

October 24th, 1981

# of Appearances

7