Alan Jackson

HISTORY WITH BILLY BOB’S:

Alan Jackson is inspired to write his hit song “Dallas” after he plays to an enthusiastic crowd. According to his liner notes on his greatest his album, “After that show, he wishes Dallas was in Tennessee.”

Kubota celebrates its 40th anniversary with a special performance by Alan Jackson. One lucky employee walks away with a $20,000 ruby.

ABOUT ALAN JACKSON:

At a time when country music is as much hip-hop and pop as anything, it makes sense that Alan Jackson would emerge with an album that has the same cleansing quality as “Here In The Real World” all those years ago. Having weathered every trend, seen “superstars” come and go, the soft-spoken legend returns with Where Have You Gone, a twin-fiddle’n’steel survey of real country. Classic songwriting that exhumes sorrow, love, life, loss, cheating, drinking, the South, wanting, children growing up and parents dying, these 21 songs are a witness to what country music was born from and will always be.

“It’s a little harder country than even I’ve done in the past,” Jackson concedes. “And it’s funny, I was driving out here where I live and was listening to the final mixes, just listening to what Keith (Stegall, his longtime producer) sent me, and I started to tear up. I was surprised to get so overly emotional, but I just love this kind of music. It’s what I’d always wanted to do.”

When Alan Jackson broke the country charts wide open with “Here In The Real World,” his unadorned classic country was a stark reminder of how gut-wrenching a simple song can be. With the chorus closing revelation, “The one thing I’ve learned from you/ is how the boy don’t always get the girl/ here in the real world,” the future Country Music Hall of Famer deployed the kind of vulnerability only a strong man of deep dignity can. Tall, thin, quiet, Jackson hadn’t come to save country music in 1990. But, somehow, that’s what happened. In the world of jacked up, arena-ready Nashville, Alan Jackson stood as a voice where bruised hearts, small pleasures, words written in red and easy good times were strung like laundry on lines of steel guitar, fiddle and a Telecaster that evoked Merle Haggard, George Jones, and Buck Owens.

Entertainer of the Year. Grammy winner. Headliner. Thirty-five #1s. Enduring hits, including “Don’t Rock the Jukebox,” “Chattahoochee,” “Gone Country,” “Remember When,” “Drive (for Daddy Gene),” “Chasin’ That Neon Rainbow,” “Where I Come From,” “Wanted,” “Little Man,” “Who’s Cheatin’ Who,” “It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere” with Jimmy Buffett and “Murder on Music Row” with George Strait. And when America was stunned in the aftermath of 9/11 and the World Trade Center falling, it was Jackson who took the stage at “The CMA Awards” and in his quiet way expressed the confusion and grief of the entire nation with, “Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning).” Once again, he delivered for a country that couldn’t find the words: simple, straightforward and hollow without buckling as only the greatest country songs can be.

“It’s been way too long since you slipped away

I just can’t forget, I can’t pretend it’s okay

No other one could ever replace you

So I’ll keep on believing and dreaming of you…”

>– “Where Have You Gone”

Alan Jackson, more than any artist of the modern era, understands the power of a song to cut loose to, shed tears to, reckon your mistakes to, even marry your daughters to. When it finally came time to go into the studio, those songs kept tumbling out. “You’ll Always Be My Baby (Written for Daughters’ Weddings)” is self-explanatory, as is “I Do (Written for Daughters’ Weddings)”; “Beer:10,” and “Livin’ On Empty” pack the same good-timing wallop as many of Jackson’s best loved rompers. “Boats and cars,” he says about the latter. “I’ve gotten so many good songs out of those things, because growing up boats and cars is what I loved to do, I still do. And a lot of the language suits country music.” As for wedding songs, “The first I wrote for Mattie’s wedding, the summer of 2017. But it was so hard to do, I told ’em, ‘I wrote this for all of you. I’m not writing another! The second just came out one day.” But as he allows, “The fun ones for me are always the sad ones, the sadder the better.”

There was – sadly – an awful lot of inspiration since the 2018 Songwriters Hall of Fame inductee released Angels & Alcohol. His mother, Ruth Musick Jackson, passed away in 2017, then his son-in-law died in a boating accident in 2018. The album that was underway was shelved, “and I didn’t really feel like making music for a couple years.” He emerged with, “Where Her Heart Has Always Been (Written for Mama’s funeral with an old recording of her reading from The Bible),” one of the most beautiful songs about leaving this world for the next, written for his mother’s funeral. After the recording was mixed, one of Jackson’s four sisters found a recording of “Mama Ruth” reading Scripture, which was added in. “That was sweet. Towards the last few years, she had a scratchy voice. But she was just such a sweet woman, a sweet, sweet lady, so we had to have that on here.”

That raw ache, the quiver at the very edge of the moment that made Jones’ country so consuming, defines the haunted “Way Down in My Whiskey,” while the lamenting “Wishful Drinkin’” with its piano flourishes and vivid images marinates in a chorus truth of “wishin’ you had never left and drinkin’ ‘cause I’m the reason you won’t stay.” With a mandolin-driven “Chain,” Jackson draws on Hank Williams’ blues for a song from a man who can’t let go of what’s gone.

“Merle and George and Hank,” Jackson intones. “A lot of young people liked that music when I was growing up, but it felt like nobody was making it. Somebody had to go to Nashville to make that kind of country. Randy (Travis) did and was great. But real country music is gone. It feels like 1985 again, and somebody has to bring it back. Because it’s not just 50-year-old people, it’s 20- and 25-year-olds. They have a real ear for country music, because it is real and genuine. They know the difference, and you can’t fake those things.”

“But I can be that whiskey in your bottle

I can be that smile that takes away your tears

I can be that place you just want to run to

I can be that something to get you through…”

— “I Can Be That Something”

To hear the giddy “Back,” a quick “Subterranean Homesick Blues” tumble through everything country life is, the ’67 Telecaster romance sparked “Where The Cottonwood Grows,” the elegant heartbreak salvage “I Can Be That Something” with its gentle invitation is to understand how much life true country music contains. It’s not bumper stickers or emojis, but a 100 proof distillation of a way of living.

“When I write, I visualize back home and growing up,” he admits. “I say this, ‘Real country songs are life and love and heartache, drinking and Mama and having a good time, kinda like that David Alan Coe song.’ But it’s the sounds of the instruments, too. The steel and acoustic guitar, the fiddle, those things have a sound and a tone – and getting that right, the way those things make you feel, that’s country, too.”

Jackson and Stegall rounded up many of the players who helped Jackson forge his ’90s modern traditional sound. Guitarist Brent Mason, drummer Eddie Bayers, bluegrass icon Stuart Duncan, steel legend Paul Franklin, as well as Gary Prim on keyboards, JT Corenflos and Rob McNelley on electric guitars, Scotty Sanders on dobro and steel and Glenn Worf, Dave Pomeroy and John Kelton sharing bass duties. “The playing was just exceptional; they played their rear ends off. It knocked me over the playing was so good.”

The feeling was mutual. Jackson explains, “I don’t know how many of them came up to me, saying, ‘I can’t tell you how good it feels to play on a real country song.’ We always cut live. I’ll go in and sing six or seven times while they’re figuring (the dynamics) out. Listening in the booth, the fiddle and steel stuff just about killed me.”

“’Cause if you’re gonna leave me, just pack up and go

There are just some things, A man don’t need to know

And I don’t wanna hear, What’s going through your head

Just take out your lipstick and write it in red…”

— “Write It In Red”

The cheater confronting “Write It In Red” with its slow cascade of fiddle and pools of steel bears that out. An adult male looks at the woman doing him wrong, acts like a man and tells her to get on with it. “You don’t hear songs like that anymore, especially when it’s the woman doing wrong. That never happens, so I wasn’t sure. I use Keith to guide me a little bit, because when you write, you’re too close to it. Sometimes he’ll say, ‘We can cut it and see how it sounds..’ So, we did.” Pausing, he now enthuses, “And it feels… incredible.”

Having written 15, found five from friends including nephew Adam Wright, who contributes the bar wisdom “The Boot” and the philosophical “The Older I Get,” co-written with Hailey Whitters and Sarah Turner, there’s a lot of life and a lot of wonder on Where Have You Gone. It’s a surprise not lost on the 60,000,000+ selling artist.

“I never felt the need to chase anything different than I did. I just did what I liked and was lucky enough to connect with people who love the same kind of country music I do. My heart was in the real country music, that was what I wanted to do, and I thought if my career lasts three or four years, I’d be happy.”

He may joke about being labeled “Merle Haggard on milk” coming up, but Jackson was true to the country that mattered to him. He’s also honoring his influence’s influence with a tender rendering of “That’s the Way Love Goes (A Tribute to Merle Haggard)” which evokes the title track of Hag’s 1983 album. “I’d heard that Haggard cut it for Lefty Frizzell, to honor him,” Jackson explains, “I’d been wanting to do the Haggard song for so long. With everything this album was, it just seemed to be the time.”

With playing so good, songs so classic, his time spent in grief lifting, Jackson, Stegall and the players found themselves waist deep in great songs. Following his longtime producer’s notion to “cut it and see how it sounds,” they suddenly realized they’d amassed more songs than a single project could contain. “There was some discussion of ‘Let’s do a double album, but do it one disc, then a second,’” Jackson remembers. “Sometimes it can be too much. If it’s a lot stuff, it can overwhelm. But the more we talked, the more I realized: people are hungry for this, and I want these songs to stand together.”

Though they barely did get by, I never saw them cry

They said when things get rough, You gotta pick yourself up…”

— “A Man Who Never Cries”

“You listen to these songs, and you realize these things are true. ‘The Older I Get’ sounds like where I am in my life, what I’ve learned and how I feel. “A Man Who Never Cries’ makes you cry. Denise (his wife of 42 years) said, ‘A lot of those lines are you, but you do cry.’ Truth is I’m pretty emotional, and I cry maybe more than she does, but it’s really about when those tears are shed.”

That emotion stains “Things That Matter” and “This Heart of Mine.” It echoes on “I Was Tequila,” a heartbreak reflection on worlds colliding, a stubborn man and the recognition some things can’t be; mirroring his very first single, the jovial optimistic “Blue Blood Woman (Redneck Man),” he looks back on what was lost – and what it truly means now that there’s been time to reflect.

“I know I’ve changed, but I’m still pretty much the same person who came to Nashville all those years ago. I still eat beans and cornbread. I fool with my cars, and I like to go outside and watch the sunset. I fool with my cars, and I like to go outside and watch the sunset…things I did when I was 20 years old. My heart’s still there. I still think like that, have those values. That’s how I was raised, so those things don’t change. I kept what I love and believe in.”

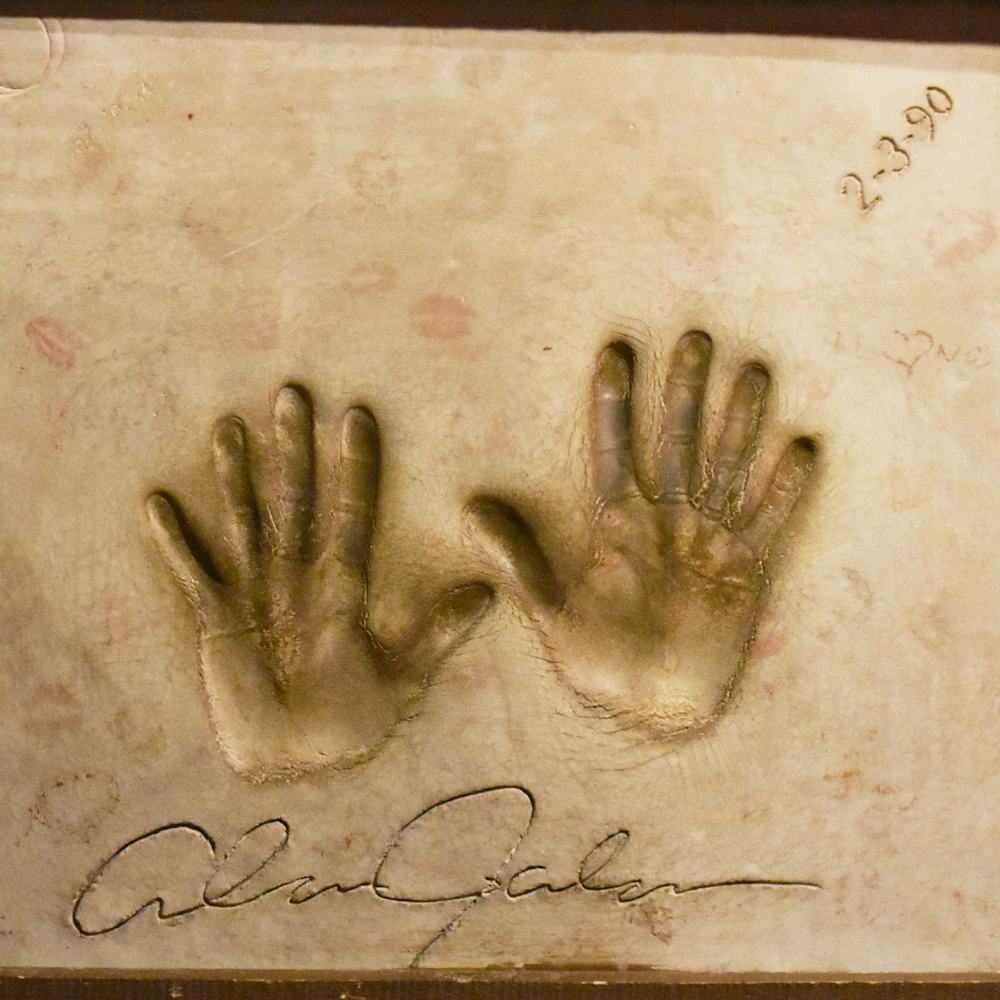

Debut Date

February 3rd, 1990

# of Appearances

3